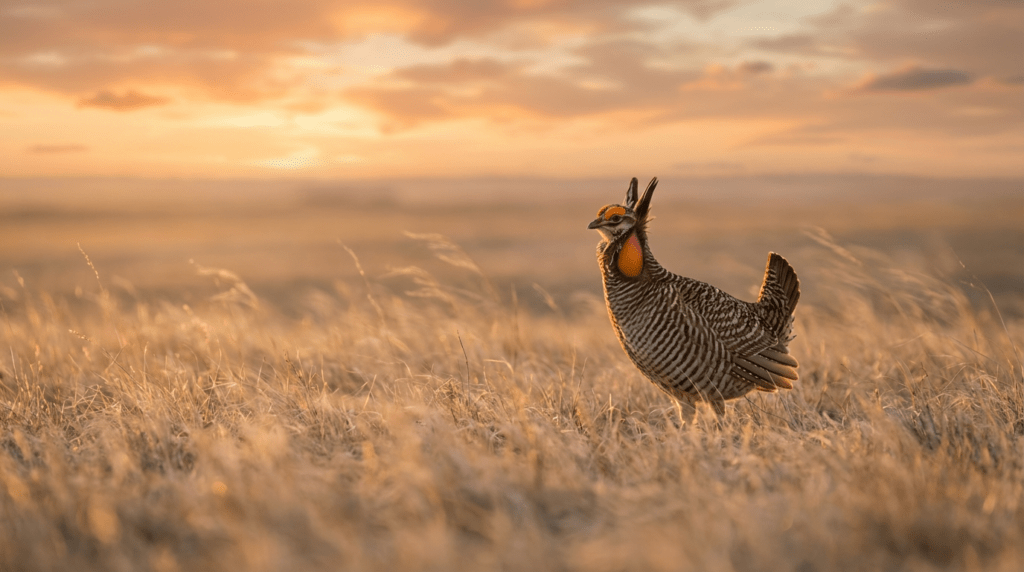

On the wide, quiet grasslands of the southern Great Plains, there’s a sound most people never hear. It’s not loud. Not dramatic. Just a low, popping, fluttering call made at dawn, when the wind barely moves the grass.

That sound belongs to the lesser prairie-chicken.

And right now, its future is sitting in the middle of a very real, very human argument.

When lesser prairie-chicken protections removed, it wasn’t just a regulatory update buried in a federal notice. It landed hard. Ranchers noticed. Conservationists reacted. Energy developers leaned in. And rural communities, already balancing livelihoods with land stewardship, were left asking the same question:

What happens next?

This isn’t a simple story. It never was. And pretending it is doesn’t help anyone.

Let’s walk through it calmly, honestly, and without the usual noise.

The Bird Most People Never See (But Should Care About)

If you’ve never seen a lesser prairie-chicken, you’re not alone. Even people who live in its range can go decades without spotting one. They blend into the shortgrass prairies of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. Subtle. Ground-dwelling. Easy to overlook.

But their role isn’t small.

These birds are what biologists call an indicator species. When their numbers drop, it’s usually a sign that the grassland ecosystem itself is under stress. Less native grass. More fragmentation. Too many roads, wells, fences, or crops where prairie once stretched uninterrupted.

In other words, when the prairie-chicken struggles, the land is telling us something.

A Quick Look Back: How We Got Here

The lesser prairie-chicken has been bouncing on and off conservation watchlists for years.

At different points, it’s been:

- Proposed for protection

- Listed as threatened

- Delisted

- Reconsidered again

This constant back-and-forth didn’t happen by accident. It came from competing pressures.

On one side, scientists tracking declining populations. On the other, landowners and industries worried about how federal protections might limit grazing, farming, oil, gas, wind, and solar development.

When lesser prairie-chicken protections were removed, it followed legal challenges and shifting interpretations of the Endangered Species Act, especially around how future threats and habitat models are weighed.

For many rural stakeholders, it felt like relief. For conservation groups, it felt like a warning bell.

Both reactions make sense.

What “Protections Removed” Actually Means (In Plain Language)

This part matters, because there’s a lot of confusion.

Removing protections does not mean:

- The bird is suddenly thriving

- Habitat loss no longer matters

- Anyone can deliberately harm the species

What it does mean is that federal Endangered Species Act safeguards are no longer automatically triggered.

That changes things like:

- Required environmental reviews

- Restrictions on certain land uses

- Federal oversight of habitat disturbance

States can still step in. Voluntary conservation programs still exist. But the strongest, most enforceable layer of protection is gone.

And that creates a vacuum.

The Human Side: Ranchers, Farmers, and Private Land

Here’s something often ignored in national debates: most lesser prairie-chicken habitat sits on private land.

Real families. Multi-generation ranches. People who live on thin margins already.

For some landowners, previous protections felt like punishment for simply owning prairie. They worried about:

- Losing control over grazing plans

- Increased compliance costs

- Uncertainty about what they were allowed to do on their own property

Many of these landowners weren’t anti-conservation. They were frustrated by unclear rules and outside decisions made far from the plains.

When lesser prairie-chicken protections were removed, some finally felt they could breathe again.

That emotional reality deserves respect, even if you disagree with the outcome.

Energy Development: The Quiet Giant in the Room

You can’t talk about this bird without talking about energy.

The southern Plains are rich in:

- Oil and gas

- Wind power

- Emerging solar projects

Each brings jobs, revenue, and infrastructure. Each also fragments habitat.

Wind turbines, in particular, have been controversial. Not because they kill large numbers of prairie-chickens directly, but because the birds tend to avoid areas with tall structures. Turbines change how the land feels to them. Predation risk rises. Breeding grounds shift.

When protections were in place, energy developers had to plan carefully. After protections were removed, some of those constraints loosened.

That’s good for speed and investment. Riskier for long-term habitat continuity.

Conservationists Aren’t Crying Wolf

It’s easy to dismiss environmental warnings as exaggeration. But in this case, population trends tell a consistent story.

Over the last century, the lesser prairie-chicken has lost over 90% of its historical range.

Drought. Land conversion. Fire suppression. Invasive plants. Infrastructure.

Remove one stressor, and the bird might adapt. Stack them together, and resilience drops fast.

Groups like the National Audubon Society and Defenders of Wildlife have been vocal because they’ve seen this pattern before. Species don’t usually vanish overnight. They fade, quietly, until recovery becomes nearly impossible.

If you want to understand their concern, this overview from Audubon is worth reading.

States Stepping In: A Patchwork Response

With federal protections gone, states now carry more responsibility.

Some are responding proactively:

- Habitat incentive programs

- Voluntary conservation agreements

- Research funding

Others are moving slower, balancing budgets and political pressure.

The problem with a patchwork approach is simple: birds don’t recognize state lines.

A lek in Kansas doesn’t function in isolation from habitat in Oklahoma. Fragmented policies can unintentionally fragment ecosystems even further.

Voluntary Conservation: Hope or Half-Measure?

One bright spot is the rise of voluntary conservation programs.

These initiatives:

- Pay landowners to preserve native grass

- Encourage wildlife-friendly grazing

- Avoid heavy-handed enforcement

When done well, they work. When underfunded or poorly coordinated, they struggle.

The big question after lesser prairie-chicken protections were removed is whether voluntary efforts will scale fast enough to replace mandatory safeguards.

That’s still an open question.

Climate Change: The Pressure Nobody Can Ignore

There’s another layer to all this, and it doesn’t care about legal listings.

Climate change.

Hotter summers. Longer droughts. More extreme weather. These conditions hit grassland birds hard. Nest success drops. Food sources shift. Fire regimes change.

Without strong habitat buffers, climate stress compounds existing problems. That’s why many biologists argue that removing protections now is especially risky.

Not because today is catastrophic—but because tomorrow might be.

Why This Isn’t Just a “Bird Story”

If you don’t live on the Plains, it’s tempting to scroll past this issue.

But grasslands are one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America. More threatened, in some ways, than rainforests.

They store carbon. Support pollinators. Sustain cattle industries. Hold soil in place during drought and flood.

The fate of the lesser prairie-chicken is tied to the fate of these systems. Lose one, and the others weaken.

That’s why this decision matters beyond birdwatchers and landowners.

Legal Whiplash and What It Does to Trust

One of the most damaging aspects of repeated listing and delisting is uncertainty.

Landowners don’t know what rules will apply in five years. Developers don’t know what investments might stall. Conservationists don’t know when protections will vanish again.

Trust erodes. Cooperation becomes harder.

When lesser prairie-chicken protections were removed, it reinforced the sense that conservation policy in the U.S. is unstable, reactive, and vulnerable to political shifts.

That instability might be the real long-term threat.

Is Relisting Possible?

Yes. And likely debated.

If population numbers continue to decline, or if new science strengthens the case, the species could be reconsidered for federal protection again.

That cyclelist, delist, relist helps no one.

A more durable solution would focus on long-term habitat agreements that survive political changes. Easier said than done, but not impossible.

What a Balanced Path Forward Could Look Like

This doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game.

Some ideas already gaining traction:

- Larger, landscape-scale habitat plans

- Better coordination between states

- Stable funding for voluntary programs

- Clear, predictable rules for landowners

Success depends on trust. And trust depends on listening, not lecturing.

A Personal Moment from the Plains

A Kansas rancher once described watching prairie-chickens dance on his land at sunrise. He didn’t see them as pests or symbols. Just neighbors. Part of the rhythm.

He also worried about paying his bills.

Those two truths coexist more often than people realize.

The challenge isn’t choosing birds over people or people over birds. It’s recognizing they’re already connected.

FAQs About Lesser Prairie-Chicken Protections Removed

Why were lesser prairie-chicken protections removed?

Protections were removed following legal challenges and reviews of population data and habitat models under the Endangered Species Act.

Does this mean the bird is no longer at risk?

No. Population concerns remain. The removal changes regulatory oversight, not biological reality.

Can states still protect the species?

Yes. States can implement their own conservation measures, though these vary widely.

How often should the keyword appear in SEO content?

In this article, lesser prairie-chicken protections removed is used naturally about 5–6 times, including the title.

Where can I learn more from official sources?

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provides updates and species profiles here:

👉 https://www.fws.gov/species/lesser-prairie-chicken-tympanuchus-pallidicinctus

Final Thoughts (No Grand Speech, Just Reality)

When lesser prairie-chicken protections were removed, it didn’t end a debate. It sharpened it.

What happens next depends less on court rulings and more on everyday choices how land is managed, how incentives are designed, how seriously long-term thinking is taken.

The prairie doesn’t shout when it’s in trouble. It whispers. And by the time the sound is gone, so is something else.

Whether we’re listening now is the real question.

Related Article: NC HOA Chicken Ownership Dispute Guide for Homeowners